The Art of Painting, 1667 It is probable that Vermeer traced his images projected from the camera obscura - that precursor to the photographic machine. We feel that his paintings are attentive to every detail in the frame, as though he had the luxury of viewing and contemplating these domestic scenes day-in and day-out. We do know that Vermeer took many liberties with his compositions, and not all details are articulately present, and some might even have been invented. Nonetheless, what lures us into his paintings' sense of completeness is light. His paintings invite us into the glowing chambers of the camera obsucra by gently receding the heavy curtains that cover the entrance into that magical box.

The Milkmaid,1657-58 Vermeer floods his paintings with light. It is not the harsh glare of the spotlight, or the diluted glow of foggy ambience, but the honest light that touches upon everything and reveals all of the subjects and objects in equal clarity. It is almost as thought Vermeer were rebelling against the drama of his countryman Rembrandt, whose light was inseparable from the composition, and who was still in the thralls of the biased chiaroscuros. Vermeer's light is separate from his compositions. It is the illuminant or the revelation to his paintings. What influences us to what is worth seeing isn't just the arrangements of the objects, but the light which puts things into view. Vermeer separated (or freed) light from the painting and made it the master instead.

Vermeer's light-infused paintings always take us aback. We as moderns are used to the illuminated, light-dependent photographs, and their infinite points of detail. It is always a surprise that a painting seems to do the same. Perhaps it is his view-finder the camera obscura, which like our modern-day camera cannot produce anything in the dark, that influenced Vermeer to use light in such a way . What he saw through the camera obscura, and probably tried to copy, was its uncanny ability to make images and colors exceptionally vivid and saturated, as thought they are bathed in light. Like the figures we see on a piece of photographic slide or the incredibly fluid and concentrated images that are on film celluloid, it is the light that makes them work. This democratic lighting system, imbuing everything within its reach, is no longer a tool, as in the chiaroscuro tradition of composing a picture, but rather is an aesthetic device – the aesthetic device - of Vermeer’s painting. And I strongly believe that when Vermeer saw everything so clearly through his camera obscura, he fell into the spell of the all-illuminated picture. His was a clear, dispassionate view that had few of the dramatic shadows and glaring spotlights so popular of his contemporaries and predecessors.

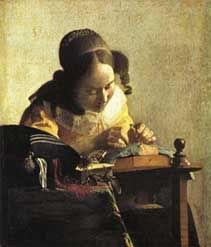

But here lies the genius of Vermeer's art. We can see everything of say the beautiful Lacemaker down to the last workings of her industrious fingers. But do we really know who she is? Light may externally illuminate her, but the secret makings of her inner world remain a dark mystery to us. Vermeer's dispersed light exposes this subtle contradiction, and make his paintings all the more poignant. We may see all the details, yet that still doesn't make us any closer to the subjects (or objects). Rembrandt's emotional chiaroscuros (even, or especially, the darkened corners) reveal more of the characters of his men and women than Vermeer's photographic light ever does. In the ambiguities of Vermeer’s art it is all exposure but little revelation. Upon freeing light from composition (and emotion), Vermeer has turned light into a warden of his subjects. He has frozen them in the enclosure of his perfect light. Yet Vermeer's strategy is a blessing in disguise. Since his unfaltering, unexcitable light cannot make his subjects tell us who they are and how they feel, his subjects become our symbols instead. We begin to idealize them. We put our own generalized labels upon them with words like “industrious”, “heroic”, or even merely “faithful”. They become our emblems of an unswerving humanity.

|

The Lacemaker,1670 In our modern world, with all these light-dependent image recording devices available at any corner store, subway station, mobile telephone and even the now good old-fashioned tourist's camera, we are in constant reach with reproduced images. At one time image production was sacred or at least time-consuming. Now the recorded image (the photographic image and now the digital image) occurs at the click of a finger and of course with the cooperation of the surrounding light. Yet we know as little or perhaps even less about ourselves as we do about Vermeer's personalities. Our quick photographic light may illuminate, but it doesn't make us any wiser? And photography, for all its modern prowess as revelation and information, still refuses to give us what the subject doesn't want us to know.

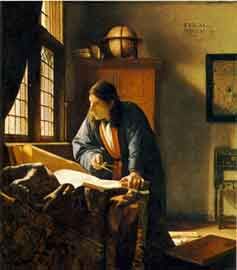

Eminent painters like Vermeer understood this and used this with such patient finesse. Some of his paintings took years to finish. He labored hard to make his emotionally distant figures into iconic representations for the human race. Unlike Vermeer, we haven’t really learned the art of patient discrimination. Everything still has to happen at the quick click of the finger. Vermeer may have been generous with his light, but he was very discerning about who received it. The Milkmaid, the Astronomer, the Lacemaker, all have somehow earned his prejudice, and with that given us an enlightened world.

The Geographer, 1669 References:Steadman, Philip.

Vermeer's camera : uncovering the truth behind the masterpieces. Oxford University Press, 2001