|

There's gentle documentary about New York Times fashion photographer Bill Cunningham, Bill Cunningham New York. He started off as a hat maker (milliner), and eventually got into fashion photography. His early major post was with Women's Wear Daily. But, after the lady's journal mocked his photographs of ordinary women in the street wearing designer clothes by juxtaposing them with wealthy socialites wearing those same clothes, he quit. He continues to take photographs of fashion on ordinary women in the streets and on socialites, and has his column in the New York Times Styles section as a regular feature.

Cunningham appears delicate and humble (I think he really is humble, but not self-effacing), but his photographic method is feline, and almost predatory. There are moments when he waits, with humped shoulders, looking like a wild cat about to pounce on his prey. He has a strange method where, still humped over, he brings his camera high above his head and takes shots of whatever is below. I think experience has shown him there is always something (or someone) interesting in the crowd beyond his sight.

New York City is his palette, and he travels throughout the city on a bicycle. He is somehow able to take out his camera and shoot the passing scene of New York's street style as he rides his bike. He has never been in an accident, at least as far as I could learn from the film, but he has had his bike stolen twenty eight times.

He wears a blue jacket, which has become his uniform of sorts. He originally found it in Paris, where it is the uniform for garbage collectors. I think he likes the sturdiness of it. He wears a plastic poncho which covers him and his camera through rough weather, and which he regularly patches and repairs.

He started out at Details magazine, where the editor would give him a hundred pages (limitless, to any photographer) to fill per issue. This freedom of creation has passed on to his New York Times assignment, where, although his newspaper space is limited, he nonetheless has the whole of New York City with which to fill his blank pages.

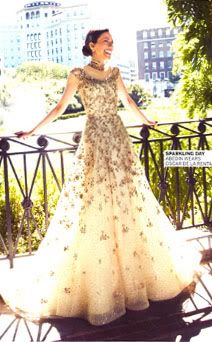

Perhaps his fame now allows him access to the most prestigious in the fashion world - famous people will stop and pose in their latest regalia for him to photograph, and famous fashion editors will sing his praises. But, I think it is his unassuming personality that convinces people. They don't fear malice or mockery from him. Through his humbleness, he also convinces everyone he meets, from the street to the gala dinners, that they are worth photographing.

He has lived for decades in a rent-stabilized artist's studio in Carnegie Hall. During the film, he was in the process of getting evicted - Carnegie Hall wanted the spaces for educational facilities. He has since moved into more spacious quarters.

He has an infectious cheerfulness about him. Perhaps that is why everyone, from people in the street who know nothing about him, to the high society in their designer outfits, allow him to take their photographs.

There was a serious, emotional moment in the documentary when he said that he goes to mass every Sunday (I think he said at St. Patrick's). He started to well-up, and it took him a while to collect himself. He gave no explanation for his emotions. I think that now in his early eighties, he must be thinking about his mortality, and his place in the afterlife. The interviewer, to his credit, left him alone.

He was drafted into the Korean War. He said it came naturally for him to wish to fight for his country. Throughout his life, his family has thought that he was a homosexual. This genuinely perplexes him, although he says he understands that a fashion photographer is not a very manly profession, in their eyes at least. But to the contrary, it needs the hardy, steely determination that he has, which allows him to do death-defying maneuvers such as cycling through New York City traffic. His determination is apparent everywhere. He even fights, in his own affable way, with his photo editor, who finally gives in to his unwavering persistence.

There were many gently funny moments in the film, but the funniest was his story of how he photographed the 1960s hippies and their clothes in Central Park, all in black and white. The psychedelics were lost in his two-toned photographs. He recounts this with his signature laugh, but that is how he told all his stories.

He calls fashion "the armor to survive the reality of everyday life." Getting rid of fashion "would be like doing away with civilization."

He has become more than a mere fashion photographer. His real subject, his muse, could be New York City.