|

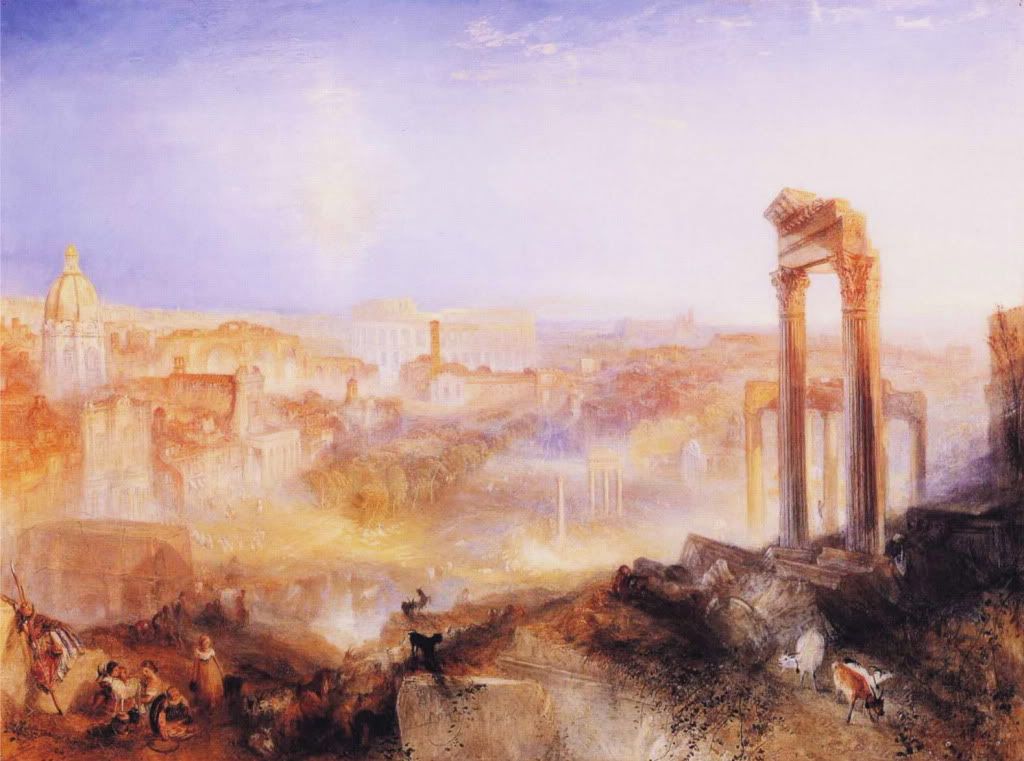

There is something both majestic and horrific about the images Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre display in their book Detroit in ruins: the photographs of Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre. The book chronicles the city's and its buildings' abandonment by its inhabitants. Marchand's and Meffre's buildings stand empty and rotting, as though they were part of a great civilization that was ransacked by invading barbarians. Destroyed hotel ballrooms and school libraries alike acquire a hauntingly grand, decadent presence. The photographs seem to aspire to the ruins paintings Turner loved to paint partly as a dedication to those ancient civilizations that preceded, and nourished, his own. But I don't think Marchand and Meffre have such lofty or grateful intentions.

The Guardian understands this horror, and starts its review of the book with an account of Detroit's abandoned police department:

In December 2001, the old Highland Park police department in Detroit was temporarily disbanded. The building it vacated was abandoned with everything in it: furniture, uniforms, typewriters, crime files and even the countless mug-shots of criminals who had passed through there. Among the debris that photographers Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre found there in 2005 was a scattering of stiff, rotting cardboard files each bearing a woman's name.Like the serial killer who destroyed the lives of the 11 women, Detroit's ransackers have done the same to their beautiful city.

In total 11 women had been catalogued by the police, including Debbie Ann Friday, Vicki Truelove, Juanita Hardy, Bertha Jean Mason and Valerie Chalk. Down in the dank basement of the police station, where "human samples" were stored – and had been abandoned along with everything else – the two French photographers also uncovered the name of the man who was linked to all of the women's deaths. Benjamin Atkins was a notorious serial killer. Between 1991 and 1992 he left the bodies of his victims in various empty buildings across the city.

Marchand's website for his own photographs displays what resemble fashion photos of models for a style magazine. None of the Detroit images are on view at this site. A few of Marchand's models are bleached blond white girls. As unattractive as all the models are, the Caucasian girls are given the brunt of ugliness, or at least of horror. They look like zombies resuscitated for the photo shoot. Or what the mad witches and ghosts from Shakespeare's plays or the Brontë sisters' novels must look like.

Many of the other models are amorphous "Asian" girl-women, doll-like both in posture and in appearance. Marchand seems obsessed with some hybrid of a Caucasian/Asian female, who is now prominent on fashion runways, as well as on the streets of Toronto. This must be the century of the "Asian look" where even ordinary folk, white or black, and mostly men, are dipping into the Asian DNA. Despite Marchand's attempt at channeling vulnerability, or even as close to beauty as he can get, there is an aura of decadence surrounding these doll-women. Some are placed in compromising poses, alluding to S&M, putting a sinister spin throughout the photographs.

The background image which surrounds the screen for his model photographs looks like one of the ravaged Detroit building interiors. And some of the shots of the models look like they were taken in those very rooms in Detroit, which Marchand seems to have taken over and converted into studios. Perhaps Detroit real estate is at give-away prices. Artists are always looking for that ideal, super-cheap location, with lots of empty space and lots of light. These are not wanting in this Detroit.

Marchand, like all artists, builds around his works to provide some kind of continuation and evolution of his ideas. From decaying, destroyed buildings to Asian hybrid, doll-like fetishistic models, what could he be trying to tell us?

Let us leave his internal monologue to himself. We see what we see. The conclusion I come up with is that Marchand doesn't see much future for America, and his photographs of both buildings and models could be seen as metaphors for the decline of America. Decadence, portrayed through racial ambiguities, sexual immaturity and the destroyed grandeur of truly beautiful buildings, is the future of America, seems to be his message. And all photographers have symbolic ideas behind their works, however much they may deny this.

Even Marchand's architectural photographs have their (invisible) racial component. Perhaps race is everything in America, something which people constantly mention, or circle around, but never confront. Detroit was a prosperous, affluent city, with "the highest median income in America." Now, it has one of the highest levels of of black crime in America, and its white population has abandoned it. From the Council of Conservative Citizens:

1) In 2000, Detroit ranked as the United States’ eleventh most populous city, with 951,270 residents. Metro Detroit, is a six-county area with a population of 4,425,110, making it the nation’s eleventh-largest metropolitan area.Marchand's and Meffre's statement on their joint website has this:

2) The city population dropped from its peak in 1950 with a population of 1,849,568 to 871,121 in 2006. In the 2000 census, 70% of the total Black population in Metro Detroit lived in the City of Detroit.

3) Detroit is usually listed as 82% black. However this is the figure on the 2000 census. The figure is much higher now as the US government estimates that Detroit shrank by a staggering 80,000 people between 2000 and 2006! Today Detroit is probably more like 90% and most of the rest are immigrants.

4) In the 2000s, 70% of the total Black population in Metro Detroit lived in the City of Detroit. Of the 185 cities and townships in Metro Detroit, 115 were over 95% White. Of the more than 240,000 suburban blacks in Metro Detroit, 44% lived in Inkster, Oak Park, Pontiac, and Southfield; 9/10ths of the African-American population in the area consisted of residents of Detroit, Highland Park, Inkster, Pontiac, and Southfield.

Ruins are the visible symbols and landmarks of our societies and their changes, small pieces of history in suspension.Despite its simplistic and pompous language (yes, it manages to be both at the same time), Marchand's and Meffre's statement makes it clear, as I had suspected, that their photographs are a false eulogy for America. The American "empire" has not yet fallen, and if so, out of the ashes fallen empires, like the Greek and the Roman, come newer and possibly greater civilizations. That is after all the course of our Western civilization. Turner was lamenting fallen empires and yet was optimistic enough to pass on meanings and symbols of hope from their ruins.

The state of ruin is essentially a temporary situation that happens at some point, the volatile result of change of era and the fall of empires. This fragility, the time elapsed but even so running fast, lead us to watch them one very last time being dismayed, or admire, making us wondering about the permanence of things.

Photography appeared to us as a modest way to keep a little bit of this ephemeral state.

Our two contemporary chroniclers simply throw pessimism, and even nihilism, at us, as though basking in the horror and unwilling to relinquish it. We don't have to accept their message.